I highly recommend you watch this month’s word, but you can also read it below.

This is the story of my daughter’s first word.

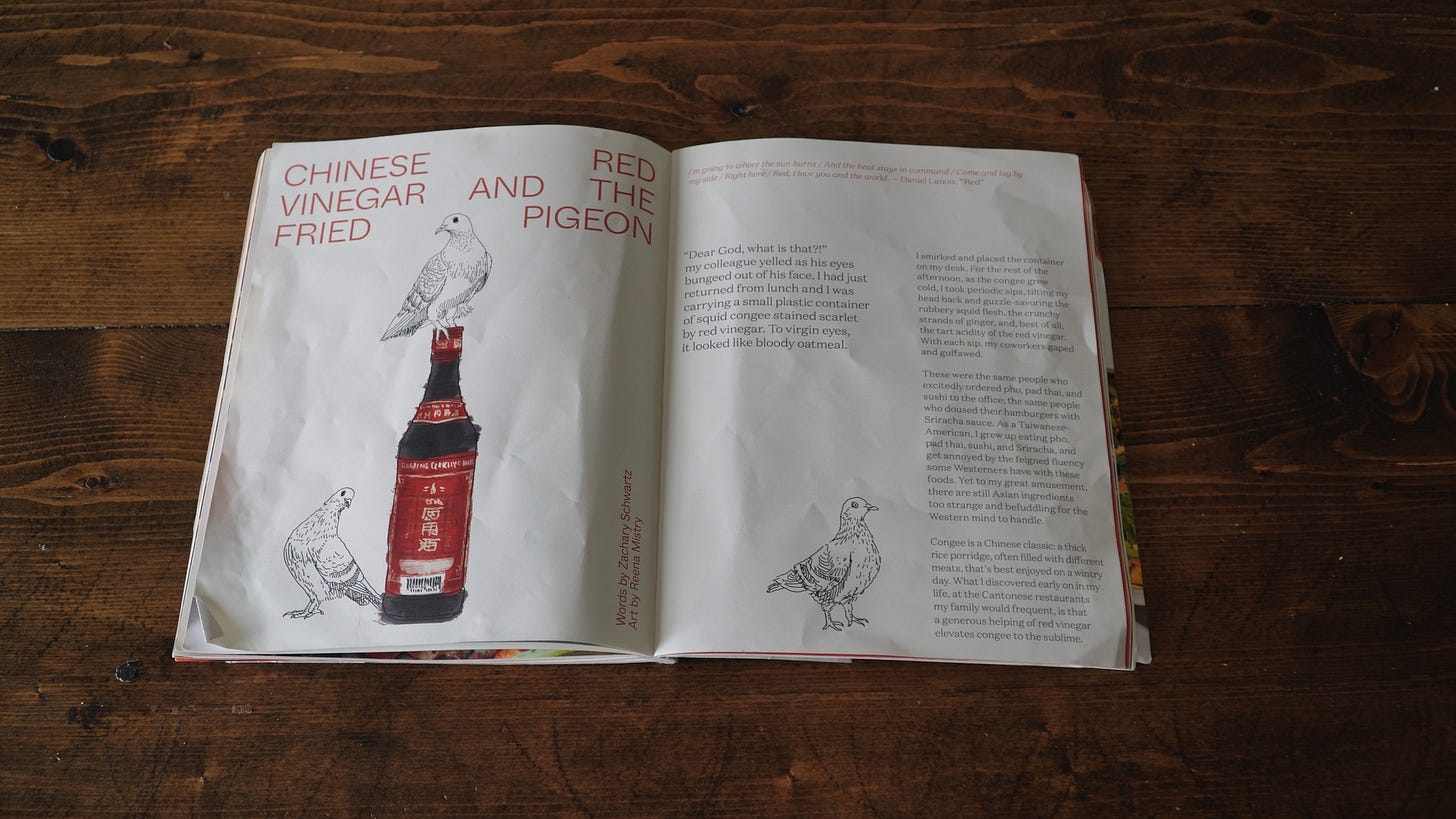

It starts with a magazine on the kitchen table. The magazine arrived with a box of premium Canadian vinegars. And she would carry it around with her everywhere and look at the colourful, food-related images.

She opened it to one page in particular, over and over again, for months. The page contained a few drawings of pigeons. She pointed to them and said…

“Dada.”

And I thought she meant me. I was her first word. But I quickly learned that it had nothing to do with me. Dada meant bird.

Until that moment, I rarely thought about dadas. They were always there, obviously, part of the background, like a park ride or a maple tree.

The more my daughter said Dada, the more I notice how they’re around all the time, yet I must pay attention to see them. Walking home from work, I discovered that there are building facades dedicated to dadas. And when I stopped to take in the Spring sunlight, I found them mingling in the crooks of the streets and roosting on silken clothing. Dadas even help express the core value of some 21st-century businesses.

There’s an argument to be made that, without dadas, there would be no airplanes. I wouldn’t be able to sit in the steel belly of a winged giant and bask in the unfiltered glory of sun rays.

Dadas can show up when I least expect it. Watching some of the VHS tapes from my childhood, I discovered one where my mom hired a magician for my brother’s fourth birthday.

My backyard looks out onto a field where geese love to fly. Every time my daughter hears them calling overhead, she runs to the door and says, “dada.”

As the months went by, her obsession with dadas grew. Dada stickers. Dada story books. Dada toys. With every new addition, I thought about them more and more, too.

Until my daughter, I rarely took the time to watch birds. Their world sidles up to mine, but it’s discreet and hard to penetrate. So this month, I tried birding. I had bought myself a fancy camera and lens to shoot One Word, and I figured I could use it to capture some video of birds.

Birding is a quiet, meditative hobby. I can tune out the digital world, the constant buzz of high frequencies, and experience the unfettered lightness of feather and birdsong.

With my kit, however, the dadas often appeared distant.

The experience convinced me that, although dadas are everywhere, getting to know them isn’t easy. They are the protagonists in their own stories and don’t have much time for interlopers.

I began to feel as if I was forcing my way, more and more, into their domain.

And it’s not just me. Starting this summer, my township plans to build a massive residence complex in the field behind my house where the dadas love to fly.

Even more concerning, the Greater Toronto Area has recently experienced a wave of bird flu, and there are much fewer geese than there used to be. There are signs at the local ponds to stay away from the birds, because they might be sick.

It’s very hard to survive as a dada, and I fear for their safety. I also worry that my daughter will get sick from splashing in a contaminated puddle or picking up a rock off the ground.

I worry for her all the time. It’s this layer of my life that wasn’t there before. She’s so special it hurts. It’s a miracle that something this beautiful and resilient and loving can exist in a world that’s so often inhospitable.

She’s defies my understanding, and has forced me to rethink what is possible.

To better understand my daughter’s love of birds, I called up an expert, and he was kind enough to let me visit his home in Peterborough.

“My name is Ken Morrison, and I became interested in birds when I was five or six years of age.”

Ken has studied birds his whole life. He was a biologist for the Ministry of Natural Resources. He’s also an award-winning bird taxidermist and runs a business out of his home called Feathers Alive.

I was shocked at his reverence for birds, which is clearly shown in his collection. He has over 130 mounts in his home, and has worked on thousnds more. During his career, Ken also donated approximately 100 mounts to the Royal Ontario Museum.

Ontario has very strict laws around raptor taxidermy, which means the birds in Ken’s collection died naturally or accidentally. Every mount Ken showed me during my tour had a story.

“That was a falconer's bird,” he said pointing to the display case. “The falconer had flown it at his home property, and he was swinging the lure to attract the bird back to his fist. Instead of coming into the lure, like it had probably hundreds of times previously, it landed on a small building and started teetering and then dropped forward and hit the ground and died of a heart attack right then. I necropsied it later and the heart had ruptured.”

We walked to another display case, and Ken pointed to two hawks mounted together and said:

“There's a story behind these two that were accidentally killed by a landowner. He put poison out to kill a skunk or rat that was getting into his beehives. The raccoon wandered away from where he'd poisoned it and died. Both these hawks died from ingesting the poisoned meat. So I mounted them as a pair with the male presenting a spruce twig to the female to line the nest with in the spring.”

Talking to Ken, I learned that dadas have a tremendous power to inspire, shape, and give purpose to the world around me.

“I consider birds important part of my life actually. I was involved in the peregrine falcon reintroduction programs in the early 80s, which was a very successful and very enjoyable aspect of my career.”

His passion and admiration for birds inspired his family, too. His wife paints birds, and his son Kyle works as a biologist in wildlife policy at the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry.

His grandchildren also love birds, and paint birdhouses and other crafts on the weekends. I’ve never seen anything like it.

“That's the Passenger Pigeon. It used to be the most abundant bird in the world. Audubon estimated about five to seven billion at one time in the early 1800s. In 1914 the last one died in the Cleveland Zoo. It was a female named Martha.”

“Why did they go extinct,” I asked.

“Because of human greed mainly, which is often the case. They were killed by the hundreds of thousands if not millions for the food market. They're salted down in barrels and sent back to New York and Philadelphia and so on. They were so abundant that they used to darken the sky for literally days. One flock flying by.”

Before we moved on, Ken said that the Passenger Pigeon was his third carving. I was stunned at the detail in his third attempt. It looked life-like.

“This is your third carving, ever?” I said.

“Yeah”

Visiting Ken’s home was an experience I’ll never forget. And at the middle of this multi-generational fascination is a father who loves birds.

And it got me thinking how there have been a few times when my daughter points and says dada and there is no bird, just a frumpy-looking bald man in a hat, and I wonder if she and I are figuring out dada together. Maybe dada means more than one thing.

Just as with birds, fatherhood was an idea in the background, a thought soaring overhead.

I’ve only had one experience with dadas, my father, and if you’ve watched or read One Word before, you probably know my dad died when I was 19. So dada for me has always been coloured a rheumy, tragic green.

Even today, my daughter is 18 months old, and I have a hard time seeing myself as a father. When I walk with her to the park or drive with her to the mall, how I feel is not how I imagined it would feel as a father. I’m just me, walking around with a little girl that I’m trying my hardest to protect.

Raising a daughter is not unlike raising a little bird. She lives in this nest I’ve created, with baby gates and extra cushions. And every day she gets a little more brave, testing the limitations of the world around her. She’s growing so fast. Some days I wake up and she looks completely different. And one day I know she’ll run to the door and fly away.

Fatherhood is absurd. I will spend countless hours raising my daughter and the goal of all this time and effort and heartache is that she must go out on her own, into this harsh, often cold and sick world.

My god, what did I get myself into?

Until I started exploring dadas, fatherhood bewildered me. But I remembered something Ken said after the tape stopped rolling. It was the concept of fledging. I called him up and asked him to explain it to me.

“When a bird is considered to fledge,” Ken explained, “is when they first leave the nest. I and several other people were involved in capturing Canada geese and bringing them to the Toronto Islands. We crated up the juveniles, the young of the year, before they could fly. The thinking is that where the birds learned to first fly, they'll come back to that general area to look for a nesting site when they're mature.”

It’s not easy teaching a little girl how to fly. Raising her takes everything, more than everything.

But as I raise her, she’s teaching me how to grow past the loss of my father, so I can be her dada. And I just want her to know, that where ever she soars, across oceans, through strange lands, down paths of knowledge, towards new friends and beyond, beyond anything I could even imagine from my place fettered to the earth, I’ll always be there when she’s ready to come home.

Dada